One of the rarest species on the planet is enjoying a balmy enclosure, greatly enhanced by the latest renewable heating technology designed and installed by Jersey Electricity Building Services (JEBS).

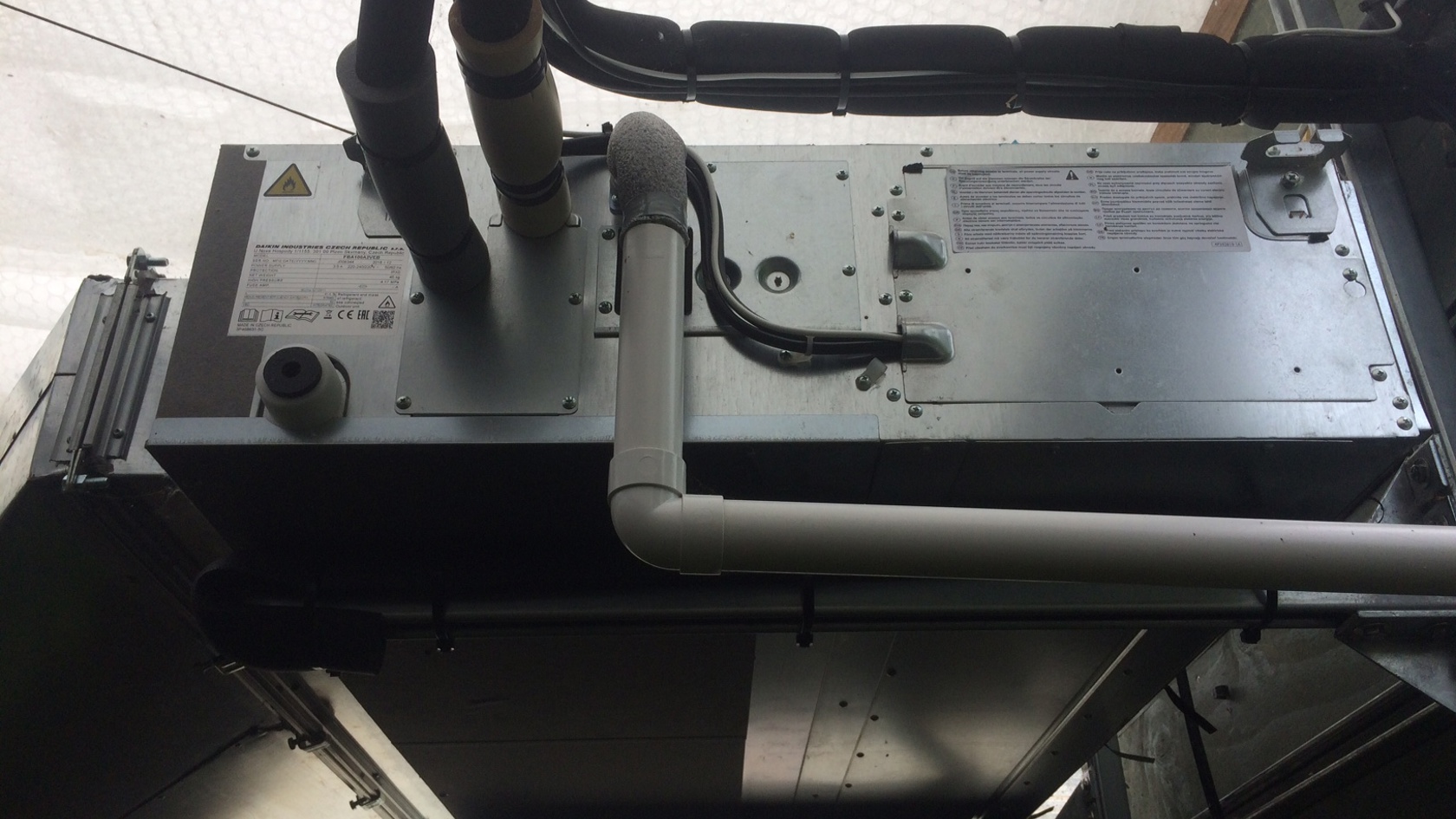

Jersey Zoo is home to 55 Livingstone’s fruit bats – the largest captive population in the world – and they need a constant temperature of between 200C and 320C to thrive. The installation of a 12kW air source heat pump (ASHP) in their 20m x 40m enclosure has proved so successful that the zoo’s Head of Mammals and bat expert Dominic Wormell is keen to install a second.

Dominic, who has been working with this species of bat for over 30 years, said: ‘Before, all we had were three 6kW spot fan heaters and a biomass boiler for winter. The more dominant bats would crowd around the spot heat and push the others out of the way, leaving them isolated and cold. Anything 150C or below damages the delicate membrane of their wings. At just 0.3mm thick it’s a very special muscle – not just skin – with a very low blood supply. A period of sustained cold can reduce the blood supply to the margins of the wings and cause damage to the delicate tissue causing holes to appear.

‘Now the heat pump is supplying warm air the length of the enclosure through vented ducting and the bats love it, flying round and round in the afternoons and roosting all over the enclosure. If they settle near the vents they start flapping their wings; it must feel like having a warm bath or shower.’

As well as providing more comfort to the bats, the heat pump is much more cost effective. By drawing latent heat that naturally occurs in the air and increasing its temperature sufficiently to heat the enclosure, the heat pump typically produces two to three times the heat that would be gained from the units of electricity used to power it – a huge saving on the biomass boiler that Dominic says can cost up to £200 a week to run in winter.

‘What’s more,’ says Dominic, ‘Buying commercially produced biomass pellets isn’t environmentally friendly. Climate change is destroying the habitats of these animals as weather patterns get more extreme. These bats are literally hanging on by a thread. There were just 1,000 left on two islands in the Comoros off the coast of Mozambique. They roost in treetops on the mountains so the recent back-to-back cyclones there could have devastated them. We are still waiting to hear the numbers from our partners on the ground there.

‘I’d like people to leave Jersey Zoo feeling inspired to save species. Habitats are being destroyed due to climate change, so this needs to be halted. It means making sustainable changes to our lifestyles, one of which is to stop burning fossil fuels. Electricity is the future.’

Habitat destruction almost led to the extinction of the Livingstone’s fruit bats’ neighbours in the enclosure, the smaller Rodrigues fruit bat from the remote island of Rodrigues in the Indian Ocean. Though still Critically Endangered, an emergency breeding programme started by Gerald Durrell himself here in 1972 means there is a thriving captive population around the world today.

‘Bats are much maligned, the real underdogs but they are wonderful animals,’ says Dominic, who admits they are his favourite creature. ‘They are eco-engineers, farmers of the forest that pollinate vast areas. Some trees have adapted to be pollinated solely by bats. The Agave plant in Mexico, for example, is pollinated by the Mexican long-tongued bat. Without that bat, there’d be no tequila.’ A sobering thought.